Chicana Psychologist Reflects on Heritage, Identity, and Belonging in Los Angeles

This is my story, shaped by generations of survival, cultural pride, and the experience of reclaiming my voice as a Chicana psychologist in Los Angeles.

I am a twelfth-generation American of Spanish and Indigenous ancestry. My family comes from the Southwest, with deep roots in New Mexico, land our ancestors lived on long before it was called the United States or Mexico. Being Chicana means honoring that complex lineage. It’s an identity shaped by colonization, resilience, and the reality of living on ancestral land where our presence has always existed, even when we’ve been made to feel like outsiders. That history is not just something I’ve studied. It lives in me. It has shaped who I am and how I do the work I do every day.

When I moved to Los Angeles, it was for more than opportunity. I came to feel something deeper. I wanted to live in a place that reflected the melting pot of identities I carry. This city gave me that. I saw my culture in the murals, the street vendors, the music, the food, and the language. It made me proud to be a Chicana.

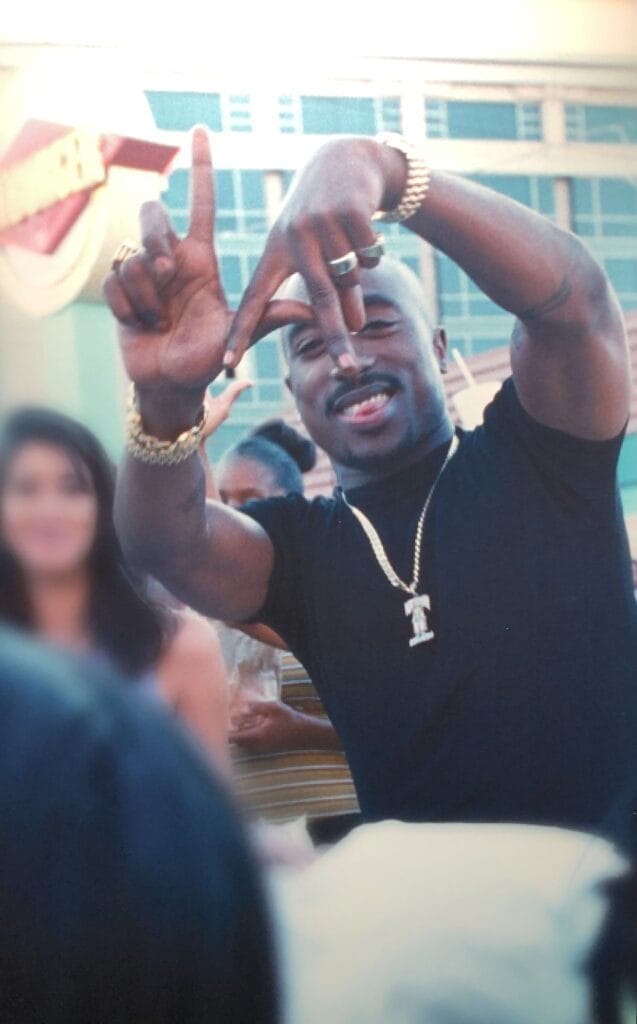

There’s a line from Tupac’s To Live and Die in L.A. that has always stayed with me:

“It wouldn’t be L.A. without Mexicans. Black love, Brown pride in the sets again.”

That line isn’t just powerful, it’s the truth. Chicanos have shaped this city and its culture in every way. And still, we have had to fight to be seen, heard, and valued.

Cheech Marin once said,

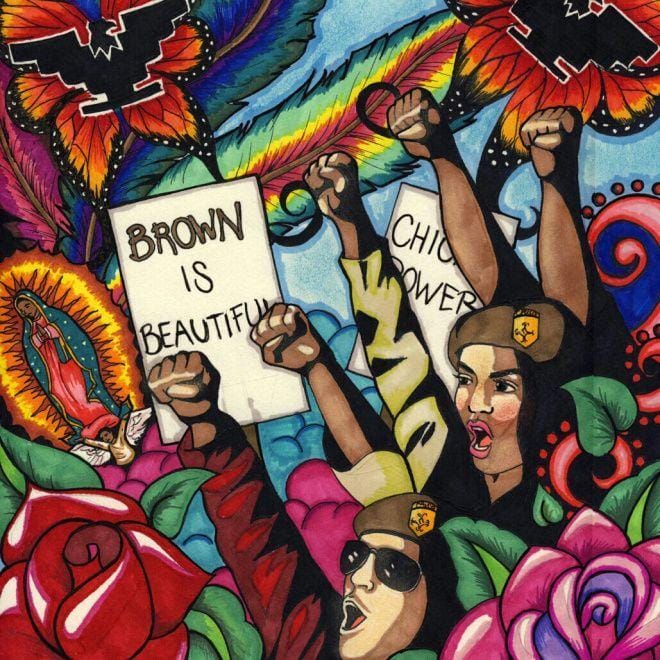

“Chicano art is American art. It’s the only art that deals with American reality from a Chicano point of view.”

That point of view matters. It’s not just art, it’s reflection. It’s history told through our eyes, not rewritten by someone else.

Source: Photograph from the U.S. Library of Congress “Picture This” blog, celebrating Hispanic Heritage murals

Lately, with everything happening around immigration and public safety, I’ve been reflecting deeply on its politics and the emotional weight it brings for so many of us who live at the intersection of resilience and grief. I’ve been thinking about how identity, community, and justice shape the lives we build and the lives we protect.

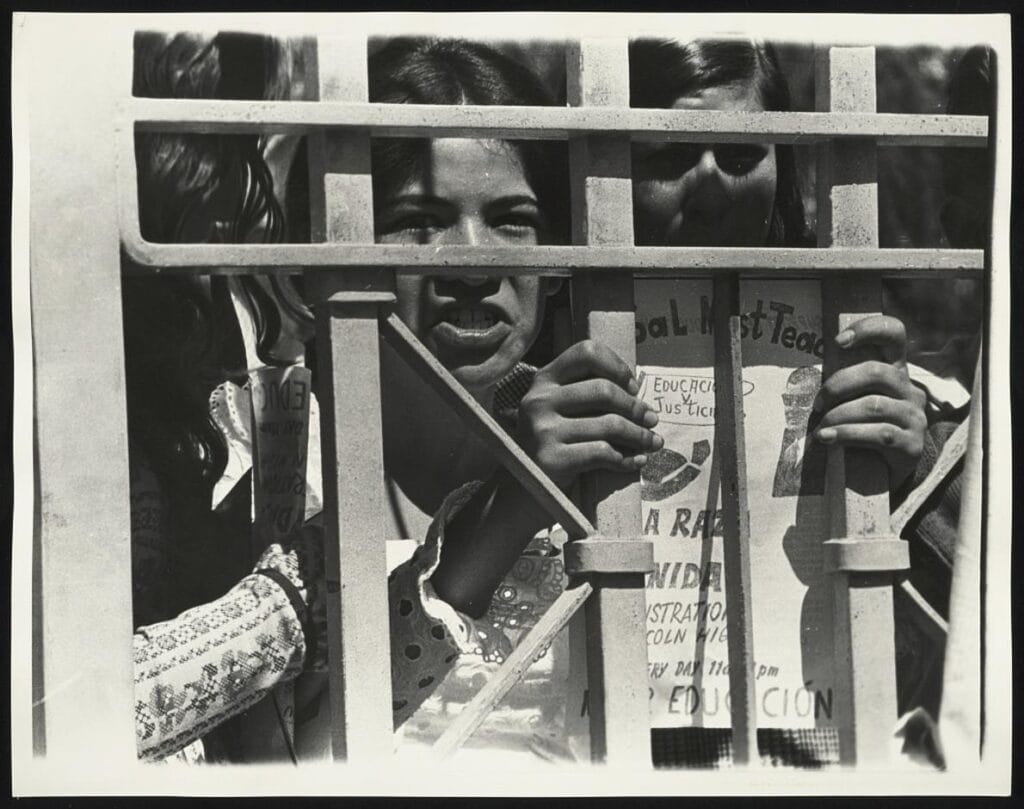

Being Chicana is more than a cultural label. It represents a history of survival. My ancestors endured colonization, forced assimilation, and systemic discrimination. In school, our families were punished for speaking Spanish. They were told to give up their language to be accepted. Many were tracked into labor instead of higher education. Many of us today don’t speak fluent Spanish, not out of shame or disconnection, but because our families were taught that blending in was safer than standing out.

That loss of language wasn’t a failure. It was a cost and a painful part of our survival.

Source: Library of Congress, American Folklife Center

I’ve experienced discrimination. I’ve been underestimated, overlooked, and told I didn’t belong. And still, I rose. I earned my doctorate. I built my own practice. I claimed space in a field that wasn’t built with someone like me in mind.

Today, I work with people who also carry the weight of generational trauma. Immigrants. People of color. LGBTQ+ individuals. People trying to reclaim their bodies, their identities, and their voices. My identity is not separate from that work. It is the foundation of it.

I believe in human dignity and the importance of safety and accountability. These truths do not conflict. They are part of the complexity many of us live with, how we love our communities, hold pride in our history, and still want a better, safer future for everyone.

I come from New Mexico, where my ancestors settled generations ago. That history is part of me, even as I live and work in Los Angeles. It reminds me that multiple places shape my culture, voice, and perspective.

Our history isn’t forgotten. It lives in our families, traditions, and how we move through the world. I will keep sharing it for those who came before me and those still finding their voice.

Carrying the Legacy Forward

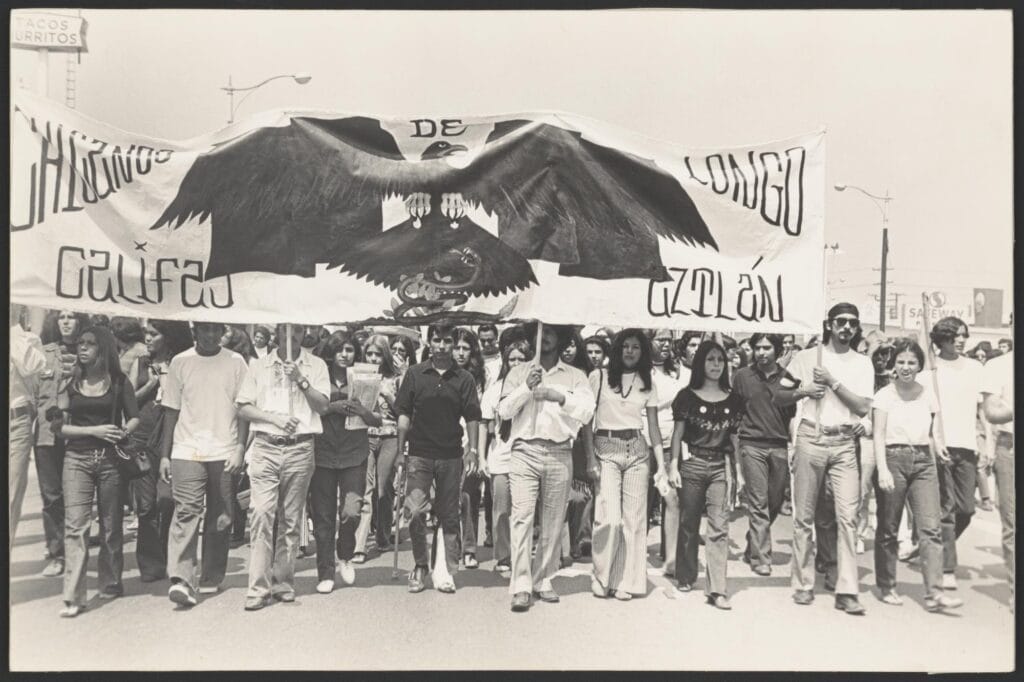

I’m sharing a clip where I talk about what it means to be a Latina at the doctoral level in psychology. Less than 5 percent of psychologists in the United States are Latinx, and even fewer are Latina women. My work stands on the shoulders of my family’s fierce commitment to education and pride. Both of my grandmothers earned college degrees and became educators. One taught her students the Pledge of Allegiance in Spanish and English, showing the importance of language and cultural identity. She received backlash from parents and the school board. I carry her ethics, resilience, and dedication into all I do. These stories live in us and drive our work forward. I’m grateful to share them with you.

My brother, Jerome J. Chavez, received his master’s degree in Chicano Studies from the University of New Mexico. His thesis, “It Was Really Up To Us”: The History of the Black Berets of Albuquerque in the Chicana/o Movement of New Mexico. His work documents a part of our history that had never been formally recorded. He has become a historian for our family and culture, ensuring our stories are preserved and honored.